PESHAWAR – On the night of 15 August, the sky over northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa did not simply rain. It burst.

Cloudbursts tore through valleys, flash floods surged down mountains, and in their path, entire villages disappeared. In the span of hours, over three hundred lives were lost and more than one hundred and fifty went missing. Swat, Bajaur, Bisham, Upper and Lower Dir, and Buner became epicenters of a tragedy now being etched into Pakistan’s climate memory.

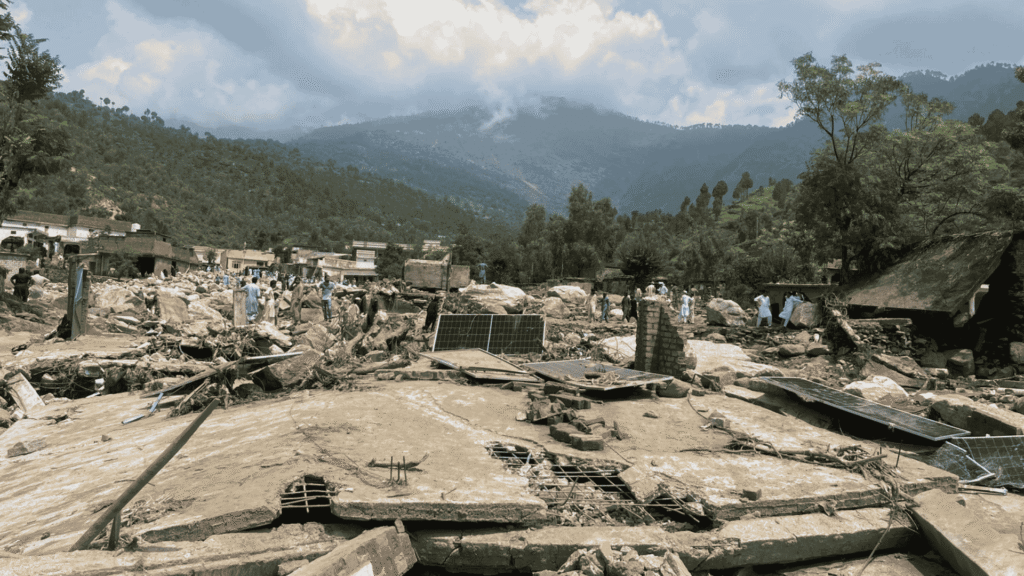

The village of Beshonai in Buner district, once celebrated for its springs, orchards, and hilltop homes, is now a graveyard. Local accounts estimate that over two hundred villagers died in that single night. Survivors continue to search for the missing beneath the rubble, rocks, and mud. For them, the name of their village is no longer a memory of beauty but a synonym for devastation.

When seasons arrive too soon

Environmental journalist Dawood Khan has tracked shifting weather in the province for years. He notes that the monsoon in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa traditionally begins in early July. This year, however, rains arrived by 22 June, and with greater force and irregularity than ever before.

“This is climate change in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa,” Dawood explains. ” The monsoon not only came early, but it has lasted longer and hit harder. If trends continue, the season may stretch into September, something that was once unthinkable.”

For Dawood, the destruction in Buner, Swat, and Bajaur is not an isolated tragedy but the visible face of a climate system breaking down.

Bishnoi: the village that vanished

Qaisar Alam of Pir Baba town recalls the Beshonai he once knew—a picturesque hamlet an hour’s walk north of the bazaar. “The water from mountain springs flowed like silver ribbons through fields. The homes sat against ridges, children played in orchards. It was like a painting.”

On 15 August, that painting was shredded. Beshonai, he says, is now “a ruin.”

Suleman Khan, a resident of Beshonai and also a local council representative, rushed back from Lahore when news reached him. “At 2:30 in the night, I arrived,” he says. “The hujra was full of bodies. Inside homes, I saw 15, 20 corpses laid out. Our village women, children, the elderly—swept away.”

Apocalyptic scenes in Bishnoi killay Buner. People looking for their loved ones beneath these boulders. pic.twitter.com/90n0nlyR7D

— Manzoor Ali (@Manzoor) August 16, 2025

He points to the rubble of his uncle’s home. “We were preparing for my cousin’s wedding on 16 August. Twenty-four people lived here. Twenty bodies have been recovered. Four are still missing.”

Suleman then gestures towards another collapsed house. “Forty-one people lived there. We found twenty-seven. Fourteen are gone. In yet another house, nine people drowned. We’ve buried seven. Two are still missing.”

He pauses before another pile of mud and stone. “This was a home. The flood carried away all five members of that family. None of their bodies have been found.” For those who remain alive in Bishnoi, grief is not measured in days. It is measured in the number of bodies still missing.

What journalists witnessed

Senior journalist Aziz Buneri was among the first reporters to reach Bishnoi. “It used to be a jewel of the Pir Baba valley,” he says. ” Now it looks like a graveyard. A small stream once cut through the village. Today it is a scar filled with boulders, mud, and silence.”

He describes how every household is in mourning. “A man searches for his brother, a woman cries for her child, another waits for her husband’s body. Every corner is grief.”

Rescue efforts, Aziz notes, are hampered by collapsed roads, electricity breakdowns, and no mobile connectivity. “Without heavy machinery, searching for the missing is almost impossible. Villagers plead for excavators. Without them, they can only dig with their hands.”

Another journalist, Anwar Zeb, counted the homes. “There were over one hundred houses here. Only four stand untouched. The rest are gone.” The floods also destroyed drinking water systems, leaving survivors at risk of disease. “Relief workers must bring clean water,” he warns. ” If they don’t, this disaster will turn into an epidemic.”

بونیر کا گاؤں بیشنوئی سیلاب سے مکمل طور پر بہہ گیا ہے، جس میں 70 کے قریب افراد جان بحق ہو گئے ہیں۔ آللہ رحم کرے آمین ۔ pic.twitter.com/WFTtozhRmz

— Dr. Rumi (@DrRumi95) August 16, 2025

The government’ response

Chief Minister Ali Amin Khan Gandapur traveled to Buner, chairing an emergency meeting in the Deputy Commissioner’s office. He was briefed that in Buner alone, 209 people had died, 134 were missing, and 159 were injured. Across seven village councils, 5,380 houses were damaged.

Rescue efforts include 10 excavators, 22 tractors, 10 de-watering pumps, 5 water bowsers, and 10 bulldozers. At least 223 rescue personnel, 205 doctors, 260 paramedics, 400 police, 300 civil defense volunteers, and three army battalions are on the ground.

More than 3,500 stranded people have been evacuated. Relief camps are distributing food, tents, blankets, mattresses, and medicines. Provincial authorities have released 1.5bn rupees (5.35mn US dollars) for compensation and rehabilitation. The Chief Minister has promised that “no affected family will be left alone.”

Beshonai village

— Shani (@FearlessWolfess) August 17, 2025

90% swept away. 10% left with nothing 💔💔#KPKFLOOD #GBFloods #bunerfloods pic.twitter.com/TGSngdZOsG

The numbers of loss

According to the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA), 314 people have died across Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in this monsoon season. Of them, 264 were men, 29 women, and 21 children. Another 156 are injured. At least 159 houses have been destroyed—97 partially, 62 completely.

The PDMA has warned of further heavy rains between 17 and 19 August, with the current spell expected to continue until 21 August. For survivors, it means that grief is accompanied by fear—that even before burying their dead, another wave could arrive.

Climate change is here

The tragedy of Beshonai and the devastation across Swat, Bajaur, and Dir is not merely a story of natural disaster. It is the story of climate change in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, reshaping seasons, extending monsoons, and intensifying storms.

Villages once known for their beauty now stand as evidence of how fragile human life has become in the face of shifting skies. For Beshonai, the disaster is personal. For Pakistan, it is a warning.