The question of whether Pakistan and Afghanistan are heading toward a full-scale war is no longer distant from ground realities. This issue raises several follow-up questions: what would such a conflict look like, which forces are pushing both sides toward escalation, and what might be the eventual outcome?

The situation on the ground appears dangerously close to open confrontation. Yet, behind-the-scenes actors continue to push for de-escalation. Parts of Pakistan’s ruling establishment and segments of the Afghan Taliban leadership still prefer that war does not break out. According to Pakistani journalistic circles, Saudi Arabia has once again stepped forward to mediate between Islamabad and Kabul.

This mediation effort seems to be the final diplomatic attempt before tensions escalate further. In other words, the likelihood of war appears significantly higher than the possibility of avoiding it. Anyone familiar with Afghanistan’s history of wars knows that the country’s natural defense lies in its harsh, mountainous terrain.

Afghanistan has historically been a battleground dominated by lightly armed fighters using guerrilla tactics. Heavy weaponry, long-range artillery, advanced aircraft, gunship helicopters, and sophisticated modern warfare tools have rarely shifted the balance in favor of invading powers.

Also Read: Pakistan at war: Fighting Terror and Betrayal

The First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842), the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1878–1880), the Third Anglo-Afghan War (1919), the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989), and the United States–NATO Afghan War (2001–2021) all followed the same pattern. Despite seizing major cities, including Kabul, temporary victors were eventually forced to withdraw. Guerrilla resistance repeatedly overturned the goals of empires.

This pattern extends further back; no external force has permanently established itself in Afghanistan. Most have ultimately chosen to step back, leaving Afghans to their own affairs.

Ideology and Resistance: Afghanistan’s Strength

A critical question arises: if Pakistan now seeks to wage a war under the banner of eliminating terrorism, what would be the likely outcome? For the first time in two centuries, Afghan fighters would prepare to fight a Muslim state. The same would be true for Pakistan.

Afghan combatants in past conflicts relied on a fusion of religious conviction rooted in Islam, a strong Deobandi worldview, and deeply entrenched Pashtun ethnic nationalism. This combination transformed their resistance into an unbreakable wall, one that foreign powers failed to overcome.

If Afghanistan were to fight Pakistan today, this ideological cement would harden once again. Their religious thinking, combined with renewed confidence in the Deobandi outlook, would merge with Pashtun nationalism. This combination could create a formidable force.

Also Read: Pakistan-Afghanistan talks reach a delicate Deadlock

The same doctrine that scholars of India used before partition, and later during anti-Soviet and anti-American wars, served as a unifying factor. Can this doctrine now prevent a bloody conflict between two Muslim countries? Current evidence from Pakistan suggests that a unifying religious ideology is unlikely to avert confrontation.

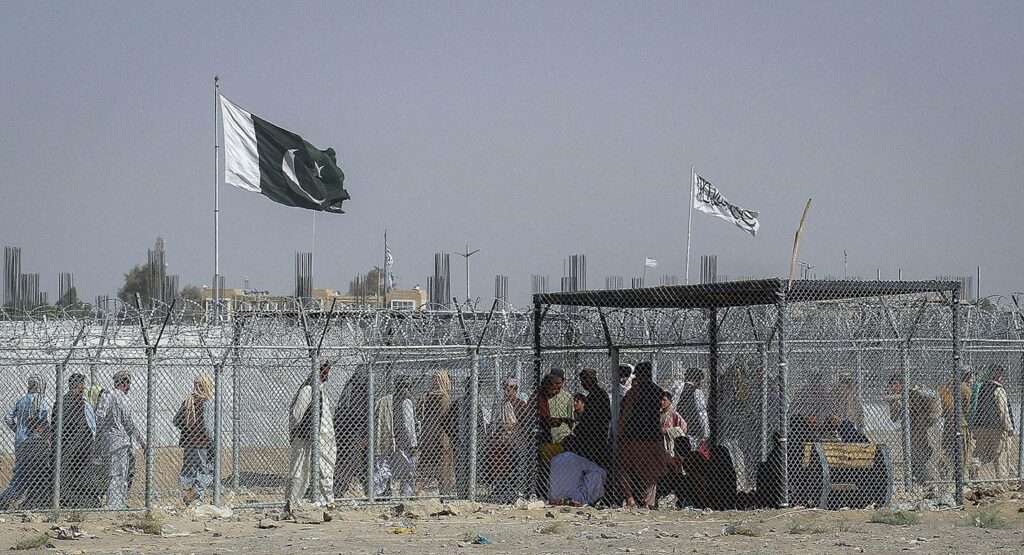

The Pakistan-Afghanistan border is long, mountainous, and difficult to control. Tribes living along this frontier act as natural scouts. The 1893 political line has never succeeded in dividing them socially, economically, or culturally. In any future conflict, these border tribes could form a critical third party, likely to remain neutral or shift decisively, with most analysts expecting them to lean toward the Afghan Taliban.

Technology, Intelligence, and Historical Lessons

Modern technology has reshaped warfare and disrupted traditional guerrilla strategies. Yet, even advanced systems depend on reliable human intelligence. The United States enjoyed extensive human intelligence networks in Afghanistan but still could not achieve strategic success. Pakistan today possesses very limited human intelligence capabilities inside Afghanistan.

Past governments supported by Moscow, Taraki, Amin, Karmal, and Najib, accused the United States, Pakistan, and others of backing terrorism. Years later, the United States, NATO, and the administrations of Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani leveled the same charges against Pakistan. Today, Pakistan directs similar accusations toward the Taliban.

Also Read: Afghan Transit Trade suspended as Pakistan orders offloading of containers

These accusations in the past triggered extremely violent conflicts, yet terrorism centers within Afghanistan endured. Geneva Accords came and went. Doha Agreements came and went. The Soviets eventually withdrew. The Americans eventually withdrew. What, then, would be fundamentally different if Pakistan also wages a war?

The British attempted to impose trade restrictions; they failed. The Soviets tried the same; they failed. The Americans tried economic blockades; they, too, could not succeed. Persian-speaking Afghans sided with the Soviets, then later with Americans. But today, in opposition to Pakistan, these factions align with the Taliban.

For the first time since 1973, Pakistan does not have a clearly identifiable support base inside Afghanistan. The British, Russians, and Americans all recognized that military intervention in Afghanistan carries enormous economic costs. Pakistan, already constrained economically and dependent on the International Monetary Fund, faces a critical question: how could it sustain such a cost if war erupts?

Also Read: Pakistan-Afghanistan border clashes intensify as regional powers call for restraint

Historically, when the British invaded Afghanistan after securing the Indian subcontinent, Muslims from Bengal to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa opposed them. When the Soviets entered Afghanistan, not only Pakistan but the entire Muslim world rejected their move. When the Americans arrived, Pakistan remained deeply opposed. Today, circumstances differ dramatically.

If Pakistan decides to undertake military action inside Afghanistan, the population of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and its tribal districts appears strongly opposed. Local political leadership and ordinary citizens express clear resistance. Given these realities, how could Pakistan enter a conflict under such conditions?

If reports of Saudi mediation prove accurate, Pakistan must make every possible effort to ensure the initiative succeeds. Mediation may be the only viable exit from what increasingly appears to be a dead-end scenario. The region’s history remains a warning, and its lessons are clear: escalation could lead to costly and uncontrollable consequences.

The article originally appeared in Daily Aaj Peshawar on 28 November 2025.